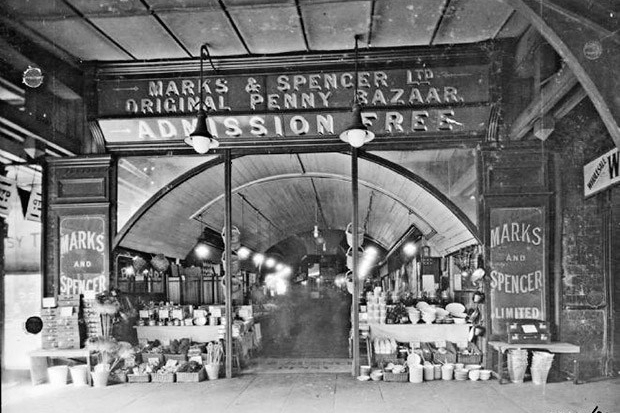

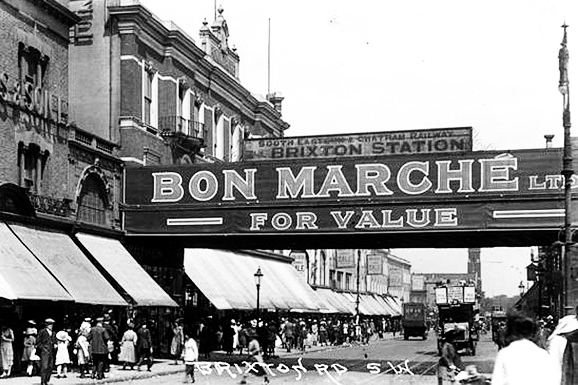

Brixton was at the epicentre of the department store’s rise in Victorian Britain. Marks & Spencer's had its first London branch there, a penny store in the railway arches (now Ashok general store at 28 Brixton Station road) before moving to the impressive art deco building that it still inhabits today in 1931. The names Quin & Axtens extended impressively down the stretch between Ferndale and Brixton roads, the entire block taken up by their colossal department store, which started in 1880. Before Bon Marché eventually took them over in 1920, the two were fierce high street rivals. The shop was subsequently acquired by Selfridges and then, finally, by the John Lewis partner group in 1940. BHS was born in Brixton, started a group of American entrepreneurs in 1928, at the time nothing in the store cost more than a shilling (5p). Another veteran of the Brixton stretch, born in the 1880s, is Morleys - still going strong today. The history of Bon Marché however, is a little more glamourous…

Brixton's high street in its Victorian heyday. Clockwise from top-left: Marks and Spencer's original Penny Bazaar; 1931 in the building it still occupies today; Christmas lights outside Quin & Axtens; Quin & Axten's long street facade; Morley & Lanceley in 1880 (Now Morley's); a Bon Marché banner on Brixton railway bridge.

The store was conceived of seemingly on a whim, by Tooting businessman James Smith, a printer by trade and owner of the Sportman newspaper, for £70,000 after his horse, Roseberry, unexpectedly won big at the races. Built in 1876, it was the Britain's first department store, taking its inspiration (and name) from the opulent Bon Marché emporium in Paris, which lives on today.

Paris' Bon Marché department store then and now.

Brixton's Bon Marché has to be understood in the context of Victorian England. The Great Exhibition of 1851 at the Crystal Palace foreshadowed the boom in British department stores. Attended by a third of the population of the time, with over 40,000 visitors a day, consumer goods and curiosities from around the globe were displayed in the magnificent structure of glass and metal, a symbol of the power of British engineering and the influence of the British Empire on display for all to see.

The Great Exhibition's astounding Crystal Palace at Hyde in 1851 and (far left) being opened by Queen Victoria

On top of that, the industrial revolution had brought about a sharp increase in the average household income, and a lot more free time, effectively creating a middle class. Department stores were an important part of this development, Bon Marché in particular, being the first steel building in the UK and glittering with its long windows packed full of the latest fashions and furnishings at never-before-seen prices. These grand, glamorous structures became city landmarks, giving areas a sense of identity and pride and promising a feeling of adventure in their maze of displays. (Bon Marché, for example, once treated its customers to a full-scale model steam train inside the shop, measuring more than 60 feet long).They signalled a shift away from the dark, low-ceilinged dry goods emporium where the shopkeeper retrieved for you what goods you needed. With Bon Marché, we see the beginning of window shopping.

This coincided with a shift in women’s roles at the time. As the average household income increased, so too did the value and expectation of women advancing the position of their husbands and families. This required a lot of clothes!

The relationship between women and department stores became a matter of public concern. The inexpensive goods carried in the shops freed women from hours of needlework and exposed them to an endless parade of the latest fashions. This was at odds with the expectation for women to provide a home-life for their family and husbands that was free from the pollution and corruption of the city. They were torn between their positions as consumers and producers. It was around this time that the medical diagnosis ‘kleptomaniac’ came to prominence.

Defined as the recurrent urge to steal, often without any apparent need or profit, it was an affliction that supposedly befell huge numbers of bourgeois women caught shoplifting in the new department stores of Victorian England and elsewhere. It became so commonplace as a legal defense that it was immortalised in the popular street ballad “Ladies don’t go thieving”. The tune pointed out the double standard that was emerging between the upper-middle class kleptomaniac and the working class thief. The problem of stealing in the stores and the scandalised lawsuits that followed became the battleground over which debates around industrial capitalism raged. Critics attacked stores like Bon Marché, saying that they never should have tempted middle class women out of their homes in the first place, under the false belief that they needed to purchase lace handkerchiefs and silk ribbons, when clearly they didn’t. But it would be easy to underestimate the importance of these items in Victorian society, something that perhaps only the women themselves appreciated, subject as they were to the immense pressures of elevating their status, and that of their families in a society increasingly obsessed with consumerism.

Bon Marché and Toplin House (right)

The stores also provided huge employment opportunities for working class women - in both the making and selling of the vast selection of wares that the stores carried. These women were mostly made to live in, in the upper floors of the building, sleeping in freezing, draughty dormitories after long days standing on their feet, and were made to pay for the terrible food that was provided. In an early call to intersectional feminism, The Sempstress ran an article encouraging middle and upper class women to show solidarity with their working class counterparts and refuse to partake in the bargains the stores were offering, instead questioning why they were so cheap. In this regard Bon Marché was also ahead of the curve, it was the first store that took the welfare of its staff into consideration, with purpose built 50 staff bedrooms. In 1906 the Ferndale Road Annexe - Toplin House - was added, with 100 staff bedrooms, 2 dining rooms and, incredibly, two underground tunnels (one for men, one for women) spanning the grand total of 70 metres between the annexe and Bon Marché itself.

Skipping ahead a few decades to war-torn London, the tunnels were used as bomb shelters from the Luftwaffe bombings during the 1940s. Trading was, of course, not easy during the war and after the bombing of John Lewis on Oxford Street, Bon Marché became a key resource for amenities and air raid essentials. Until, in May 1941 the building was gutted in its own bombing. The store did its best to recover, though the upper floors were to remain unused for the next decade. After a year or so its sales figures were again respectable, particularly given the circumstances. It took more than ten years to get a building license to repair the damage done in the war - the large hole in the building’s facade for example! - and business was slow. After a steady decline that was to span the next twenty odd years, Bon Marché finally stopped trading in June 1975.

Staff at the Bon Marché leaving party in 1975

The losses continued in the building’s various reincarnations - including an attempt to set it up as an indoor market and subsequently its £1 million purchase and £3.4 million refurbishment by British American Tobacco Industries (BAT) in 1982, resulting in 70 retail units and an excess of £1 million in losses in its first 4 years. Eventually it was split into individual retail units for high street names such as Dorothy Perkins and Topshop, which proved successful in the regeneration of Brixton town centre. The unit on the corner of Brixton and Ferndale road has been home to a number of pubs over the years, including The Flourmill and Firkin, The Goose (2003-2008), Ivan’s retreat (2008-2009), and ultimately The Rest is Noise, which said its last goodnight in 2011. The space is now occupied by TK Maxx.

Toplin House in its current incarnation as The Department Store, a creative workspace

Toplin House was sold in 1955 and had a number of subsequent occupiers, including the British Refugee Council, until 2012 when the site fell vacant and was squatted. Architects Squire & Partners purchased the delapitated building in 2015 and, alongside craftspeople and furniture builders as well as the contours of the original building itself, preserving both the bones of the original building and some of the graffiti from its years of vacancy, have restored it to offer creative workspaces.